Regional Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction 2023 - Europe and Central Asia

The Regional Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction 2023 for Europe and Central Asia presents three broad, interconnected risk drivers that contribute to characterizing the complexity of risk management in the region.

On this page

"This report captures the challenges and opportunities in the Europe and Central Asia region. It highlights the cost of inaction or what happens next if we do no not take urgent action in line with the recommendations for guiding national, subnational and local actors on DRR. At the midpoint of the Sendai Framework period, now is the time to take stock of progress and transform our collective actions to truly reduce risk, save lives, and avoid preventable losses and damage. "

— Mami Mizutori, Special Representative

of the UN Secretary-General for Disaster Risk Reduction

Key drivers of risk

Driver 1: Climate change and environmental degradation

Climate change holds global significance, impacting people and ecosystems around the world. This report zooms in on the specific details of how climate change plays out in the Europe and Central Asia region, with the goal to explore the key factors related to climate change and present a clear picture of the current situation in this part of the world.

Driver 2: Interconnected and complex economies, societies and infrastructure

This report takes a closer look at how the increased interconnectedness of economies and systems, along with dependencies within the region, has influenced changes in infrastructure investment and priorities. The analysis specifically explores the transformation of aging grey infrastructure and the increasing preference for green and blue infrastructure options. The COVID-19 pandemic and the ongoing conflict in Ukraine have underscored the inherent vulnerabilities in the economies, societies, and infrastructure of the region. By examining the wider consequences of these events, the report offers insights into their impact on the region's economy, infrastructure, and trade systems.

Driver 3: Changing demographics

Being a significant global crossroads for centuries, this region has experienced substantial changes in demographics. Factors like disease, conflict, borders, political boundaries, integration, urbanization, migration, and economics have all played a role in shaping the demographic profile of the Europe and Central Asia region. These changes have a direct impact on how we perceive, create, and manage disaster risk. This report delves into the consequences of these demographic shifts on disaster risk and investigates their influence on how disaster risk is created, managed, and understood within the region.

Challenges

Challenge 1: Reducing the risks of extreme wildfires

Climate change, human behaviour and other factors are creating conditions for more frequent, intense and devastating wildfires that affect a growing number of countries, people and sectors during longer seasonal periods. These evolving conditions require a shift from fire suppression to prevention, to better integrate realistic societal behaviour, to improve awareness and to provide risk information. For reducing risks tangibly, it is also critical to tackle the health impacts of wildfires and to improve the role of science and technology in wildfire risk reduction.

Challenge 2: Shifting to resilient infrastructure

There are opportunities to prevent risk and build the resilience of new and existing infrastructure challenged by the effects of climate change and obsolescence, as well as by multinational and multisector interdependence. Such resilience will not be obtained without robust and interoperable data and standards, a legislative and regulatory environment adapted to the complexity of infrastructure systems, as well as more systematic investments in prevention and green and blue infrastructure.

Challenge 3: Addressing cyber challenges and opportunities

New risks are emerging due to disruptive dual-use developments in cyberspace, while acknowledging the unprecedented range of opportunities of new technologies. The systemic digitalization of economies requires the integration of cyber risk into national risk assessments, strengthened understanding of cyber risk and the development of cyber risk-informed strategies and capabilities to withstand hybrid and cascading risk scenarios.

Challenge 4: Managing technological risks

This challenge focuses on the critical essence of technological hazards and the importance of considering technological risks in disaster risk reduction (DRR) strategies. Prevention of such disasters must be maintained as an objective through improved data collection and data sharing, and better consideration of emerging technological risks. This goal is achievable based on cooperation among competent and expertise-rich institutions with social support and good governance. Particular and urgent attention is required to understand and mitigate new rapidly emerging risks made possible by recent developments in artificial intelligence, including potential global extinction risks from uncontrolled artificial superintelligence.

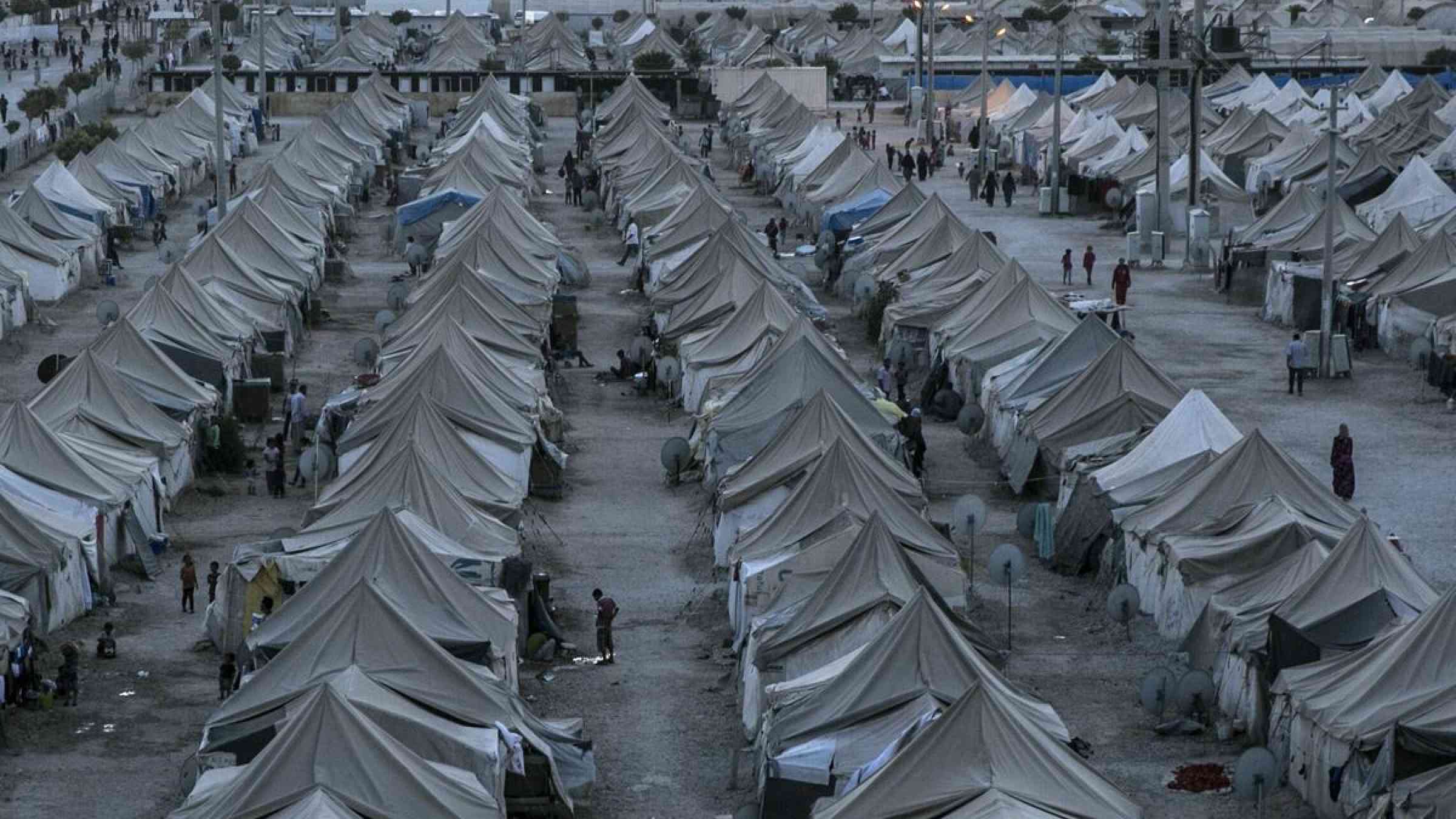

Challenge 5: Considering disaster displacement and risks faced by internally displaced people and migrants

Growing regional challenges are posed by disaster displacement and the specific disaster risks faced by displaced people and migrants within the region. Tackling this issue requires mainstreaming indicators related to disaster displacement into disaster damage and loss databases to assess the risk of future disaster displacement regarding scale and locations. A longer-term vision is also needed to strengthen the understanding of how climate change and related hazards could intensify disaster displacement and to develop policies that include migrants in risk reduction efforts.

Good practices

Good practice 1: Inclusion of disaster risk reduction in the policymaking process

Public policies are essential instruments in the governance of any political field. Many factors influence public policy formulation, including expert advice, social norms and priorities, international trends, interest groups and other contextual aspects.

Croatia

Case study

Croatia provides a particularly interesting example of the impact a focusing event can have in producing comprehensive and meaningful change involving several actors. On 22 March 2020, an earthquake struck Zagreb, damaging the city centre and many of its historic buildings. At the time, Croatia did not have well developed post-earthquake damage assessment mechanisms.

Immediately following the event, the University of Zagreb initiated a rapid post-earthquake assessment process. Within the next 2 days, the assessment process was established and ready to use on an online platform. Next, the post-disaster recovery legislation was created. The Croatian Chamber of Civil Engineers, the Croatian Chamber of Architects and the University of Zagreb had a crucial role in creating the Law on Reconstruction of Earthquake-damaged Buildings. When another earthquake struck 9 months later, in December 2020, members of the Croatian Centre for Earthquake Engineering had become regular members of the Civil Protection Headquarters, advising on better recovery after the earthquake.

Good practice 2: Creation of scientific knowledge

Scientific advice should be based on rigorous studies and solid empirical grounds. It is of utmost importance that sufficient funding is in place to accomplish such research. Country experts have investigated how DRR research is funded nationally and internationally.

Montenegro

Case study

The BALANCE project, financed by the European Union, gathers a consortium of academic and civil protection organizations from Albania, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Greece, Italy, Montenegro and Spain. The project aims to improve the civil protection preparedness and response capabilities of Montenegro in dealing with disasters that require joint response coordination facilitated via the European Union Civil Protection Mechanism.

Good practice 3: Transfer of scientific knowledge on disaster risk reduction

Scientific knowledge about DRR is of limited use if it is not communicated among relevant stakeholders. There are several mechanisms for science–policy interaction on the European level. In the DRR field, the UNDRR Regional Office for Europe and Central Asia is driving a wide range of networks and initiatives.

Italy

Case study

In Italy, an important and continuous mechanism for science–policy interaction in DRR is the collaboration between the Italian Civil Protection Department and competence centres. Emphasis is placed on the possibility of establishing networks of competence centres for the development of specific topics on integrated themes and in a multi-risk perspective.

The Italian Center for Research on Risk Reduction also aims to create a network of multidisciplinary competencies to carry out prevention and preparedness activities for civil protection and, more generally, towards DRR with a multi-risk, multisectoral and systemic approach.

Good practice 4: Adoption of a multi-stakeholder approach for disaster risk reduction

The social and environmental consequences of disasters are increasingly complex and intertwined. Innovative strategies are needed to manage risk and attenuate impacts. Multi-stakeholder platforms gather multiple organizations at different scales of governance that strive for more coordinated and integrated DRR actions and can effectively support complex impact mitigation to foster a more proactive and adaptive risk governance. The UNDRR Making Cities Resilient initiative is an example that promotes multi-stakeholder involvement at the subnational level. Through it, many cities have undertaken strategic approaches to integrating DRR in their planning.

Good practice 5: Fostering of policy coherence for disaster risk reduction

The 2030 Agenda embraced universal goals applicable to all countries regardless of their level of development. It moved the focus away from the symptoms only to addressing the underlying causes of economic, social, environmental and governance challenges. SDGs and their operational targets are indivisible, universally applicable, and global priorities that incorporate economic, social and environmental aspects and recognize their interlinkages in achieving sustainable development.

Good practice 6: Acceleration of risk-informed investment for resilience

Accelerating risk-informed investment in DRR for resilience means supporting the resilience of the finance sector itself and ensuring that investments are resilient. The financial services sector must become more resilient to external shocks and stresses. Dynamic, non-linear risk will increasingly characterize disasters in the twenty-first century. Disaster risks must therefore be integrated into investment decision-making: to do so, the finance sector should better understand hazards, and their interconnections and possible impacts.

Good practice 7: Building on a strong foundation of good governance and financial sustainability in cooperation

Disaster resilience is often not prioritized because it is wrongly perceived as being politically risky. It is an upfront cost for an outcome that might never come to pass within a political term, in most cases driven by lack of visible and well-communicated incentives. This sets in play a vicious cycle where the cost of disasters is rapidly rising, hindering governments in their ability to mobilize and provide necessary resources, and trapping them into emergency response. Although there has been progress in upgrading investment into risk reduction, there is still a bias towards reliance on ex post response, reconstruction and rehabilitation, rather than ex ante risk reduction.

European Union

Case study

In reaction to the unprecedented economic fallout precipitated by the COVID-19 pandemic, the European Commission agreed on a Recovery and Resilience Facility as its economic stimulus package. It was focused on reviving and modernizing the European Union economies in the spirit of “building back better”. NGEU is an expenditure programme of €750 billion that is structurally embedded into the European Union multiannual budget for 2021–2027. The total amount of European Union spending for building back better and the European Union Green Deal amounts to more than €1.8 trillion.

In May 2021, the European Commission announced a package of measures on sustainable finance. These included new implementing rules (delegated acts) on climate change adaptation taxonomy, which covered DRR. The regulation established technical screening criteria for determining whether an economic activity contributes substantially to climate change mitigation or climate change adaptation and does no significant harm to any environmental objectives. The rules are detailed technical criteria that companies need to comply with to win a green investment label in Europe. They consider the need to prevent climate- and weather-related disasters and manage risk of such disasters. The taxonomy is important for private and public finance.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1: Improve our understanding and communication of systemic risk

Enhance a collective understanding of systemic risk by developing more robust disaster loss tracking systems, incorporating disaggregated data to enhance the precision of policy analysis.

Recommendation 2: Build resilient societies with inclusive tools

Invest in diverse approaches to understand and attribute risk creation. Acknowledge and address biases in the development of financial, regulatory, and behavioural tools that should reflect shared priorities among risk science, policymakers, and communities.

Recommendation 3: Focus on reducing vulnerability and enhancing preparedness

Prioritize efforts to reduce vulnerability and enhance preparedness by actively working to prevent hazards, especially those with potentially catastrophic and existential impacts from which recovery is impossible.

Recommendation 4: Integrate policies with broad-based, inclusive participation

Support integrated policies to manage risk with the commitment to involve a diverse range of stakeholders. Consider the changes in exposure brought about by new investments and infrastructure. Foster detailed communication and cooperation across local, subnational, national, regional, and global processes.

Recommendation 5: Make finance work for resilience through smart investments

Ensure that investments in new systems, structures, and assets consider the creation of new risks. Encourage inclusive and equitable participation in discussions about public investment and private regulation to make development more resilient.